May 18–Jul 18, 2023

Online

-

1/11: Faraz Ravi, Snap, 2022

-

2/11: Faraz Ravi, Broken, 2022

-

3/11: Faraz Ravi, Onlooker, 2020

-

4/11: Faraz Ravi, Open Wound, 2022

-

5/11: Faraz Ravi, Floating Ladder, 2021

-

6/11: Faraz Ravi, Rupture, 2022

-

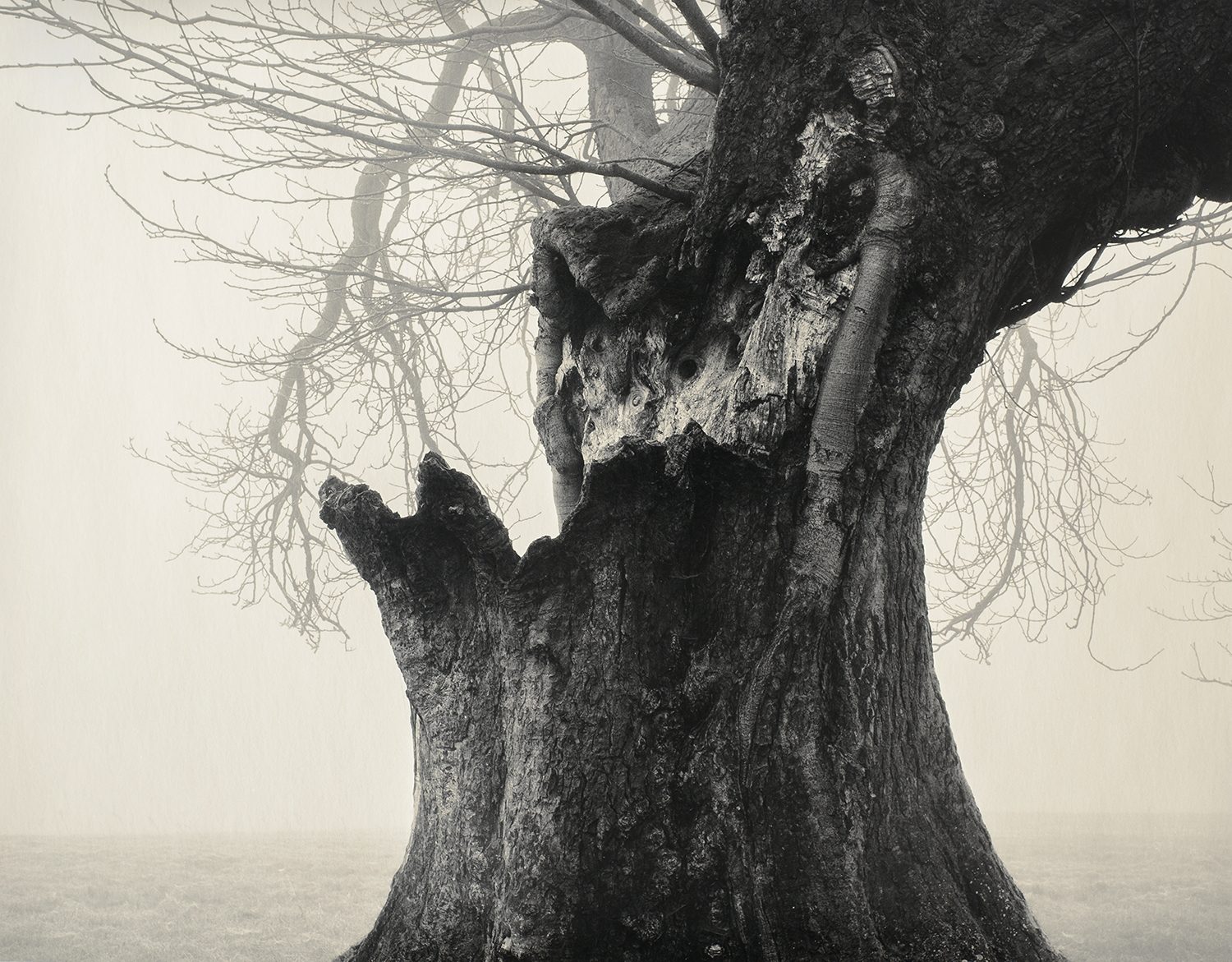

7/11: Faraz Ravi, Monster, 2023

-

8/11: Faraz Ravi, Path, 2022

-

9/11: Faraz Ravi, Forms, 2022

-

10/11: Faraz Ravi, Visitor, 2020

-

11/11: Faraz Ravi, Over Icy Water

Faraz Ravi is a photographer living in the UK whose practice focuses on the changing landscape that reflects society. Ravi primarily works in analog utilizing large format, medium format, and 35mm cameras on black and white film using silver gelatin process and toning methods in the darkroom. Being a part of nature is important within Ravi’s work, since capturing the landscape as it changes is key in his practice. Going with the flow is a necessary step in his process, he accepts mistakes and often talks through them as a learning experience. The relationship between trees and their open environment around them is a focus for Faraz as he walks through the spaces he photographs.

Silver Eye Scholar and Point Park University graduate Jen Collins writes:

“I was drawn to Faraz Ravi’s work when I first discovered him because of his attention to detail within the frame. I love the texture that he captures, how he considers the space, and his process. Since Ravi’s medium is film photography, he works in the darkroom to create these stunning images of his surrounding environment where he mostly focuses on trees. I love learning about other photographer’s processes and workflow. I connected to his darkroom work as it is a practice I appreciate and value, seeing artists continue to utilize this approach is important since it is a crucial part of photographic history.”

Collins speaks with the artist about his creative inspiration, darkroom practice, and projects.

Jen Collins: I am interested to learn more about Season of the Fallen. Could you talk more about the self-awareness of trees and your inspiration for shooting after a storm came through a landscape?

Faraz Ravi: So like a lot of projects, it's not been a case of going out and predetermining what it's going to be and trying to work within that framework. A lot of these projects have sprung up during the lockdown period, which I wasn't really able to venture very far from home. So this was a case of frequenting my local woods and several wooded areas around where I live. And some of it's quite beautiful, it's mostly oak, birch, and other species. But I've been struck by how beautiful some of the forms are in both the vibrant living forms, but also in the destructive forms. And then just seeing an inevitable parallel with how society was coping with the stormy feel of the pandemic and how these structures seem to do something similar.

And so part of what I'm driven by is this notion that there is an essential essence to things, which is a very non-postmodern idea, it's quite the opposite, but there's essential nature to things. So I’ve just been repeatedly going back and back and back to the same location, sometimes even seeing quite magnificent structures and trees. And then a year later, two years later, they've been hit by a storm and either been destroyed completely or partially destroyed and capturing them at different stages. And then I put together this narrative of destruction, but also resilience. And there's something I think slightly uplifting about that, which a lot of artists aren't really interested in anything uplifting, but I am and so this is composing that narrative visually.

JC: I feel the same way about photography. I try to look for a more positive meaning because there's so much focus on the negative, which isn’t a bad thing, but it’s good to have that mindset as well. When I was looking through your images, I felt like trees mirror lightning bolts with their branches and their physicality.

FR: There's also something intriguing, which is the lung-like structure. So a few years ago, I got pneumonia, and I got an x-ray of my lungs and it's really tree-like. There’s nothing specific here about that or really drawing on it too heavily, but I'm conscious of the fact that during the whole pandemic there are lungs that were being affected and sort of destroyed in a way and there's a mirror in that in nature.

I think what also feeds into all of this is a recent understanding, which has come through research, that a tree is a form of, I wouldn't say sentient being, but certainly there is an intelligence of thought and their abilities to communicate and react. They’re dynamic, responding to and even making decisions to respond to a situation. So suddenly, they go from this very static and barely living thing, we understand that they are living but we don’t appreciate that, to being far more interesting.

JC: It seems that walking may be directly linked to your creative inspiration. Is this so? How does this physical process fuel personal creativity for you?

FR: You have to walk to these places, it’s the nature of the place, and certainly feeling what that atmosphere is, experiencing it, and then you have a creative choice, right? Is that what you want to communicate visually? Being very consciously aware of the physical environment and the spatial relationship between things and how it feels in person. Doing the work, suffering the walk, and accepting that you may go out for hours and come out with nothing is, for me, a really important part of the process. In that you’re forced not to attribute value to effort, which is a strange way of putting it right? So just because you've gone and walked, it doesn't mean that you deserve anything. It doesn't come that way. It’s quite liberating, in that effort is a prerequisite, but it's not proportional to what your outcome is.

That is reflected when I print, I might spend hours in the darkroom and it doesn't work. I have to abandon the idea that it is just not going to print. I'm not going to get what I thought of, and it's paralleled in there. So, I like walking, I like being outdoors, if I come out with something I'm happy, if I don't I’m happy.

JC: You have been working on photo books, having two listed on your website right now, what was the process like for creating these? How did you come to select, edit and sequence the images, the theme, etc?

FR: Like most things there are a lot of failures and prototypes. I’ll go through several iterations, coming up with completely different sequences. I'll take my time and look at it in different frames. When I believe it is starting to feel right, I'll then have to print. The prints are very hard to capture, a lot of the images in the early drafts are just scans of negatives. I have to replace them with actual images and that’s a bit of a lengthy process. And in this case, I have some text to go with it that I've been authoring and writing over time. So yeah, it's really just having a stab at how it feels. Does it work? Does it elicit the kind of response I want it to? Is it becoming too tedious at times, and sometimes it does, you know, your sequence of images, saying the same thing. And I will sometimes pull an image I like just because it doesn't work in sequence.

JC: Are you drawn to book-making more than other forms of expression, such as exhibitions? If so, why?

FR: At least for now, I'm drawn to bookmaking, I like the physical. I like books, I have many photo books myself. I do like that format, it is different to viewing a print in person, for sure, especially when it comes to silver gelatin prints. I'm hoping that once I have the book I will follow it up with an exhibition of some of the works in it.

JC: You primarily work with film, why do you choose to utilize the darkroom?

FR: The film, the dark room, for me, is a constraint, right? It's a constraint which I find useful for creativity. I have a digital camera I use for family shots and that sort of thing. But when it comes to doing something artistic there needs to be a portal for random stuff to happen. You need to have a high tolerance for failure and digital doesn't allow you that when taking a photograph. Your immediate concern is looking at the back of the camera and seeing what you've got. So, between the capture and the realization there isn't much going on. What I like about film is the nature of working with the materials, the tactile sense of it, and the satisfaction of doing it. But the gaps it gives you between capture and realization of the image and the opportunities that those gaps have for you to inject something of yourself into that process is what it’s about.

Then when you go into the dark room, you're doing that again. You're taking that soul that's been exposed in the scene, you're exposing onto paper. There's something also, I mean without sounding too pretentious, quite poetic about that is that when you end up with the final print, you're also conscious of the light that formed the image came through a negative which itself was formed with light of the scene itself.

JC: Why do you think that it is important to continue utilizing this method of photography?

FR: I think it's important that it continues because ease and facilitation does not beget creativity. They're just tools in the end. However, ending with a physical artifact which is unique because when you produce a print, you can’t exactly produce the same thing again. It’s been produced by the hand of the person that took the photograph making the whole process carry more weight and meaning.

JC: I agree with you. I think with digital, at least I know whenever I was first starting out, it seems like you take so many pictures. It’s such an instant thing, like you said. Film really slows you down and makes you actually think about it.

FR: Absolutely. I mean, talk about a large format camera. You might go out and spend an hour on a shot. Maybe you take two sheets just to be safe. And that's it. You've taken the time to log the scene. Probably screw up a few times. And finally take it.

JC: On your Instagram account, you are sometimes honest about the mistakes as well as successes that come with hand-printing. Do you have anything further to add about this process?

FR: I think you have to accept failure. So for example, recently I developed some film I took a few weeks back. And I'm really trying to decide what developer I should use, so I decided on PMK. I got an image I was really pleased with. But the development process was uneven and so it's unusable. And I'm just looking at this negative thinking, this could be such a beautiful print. And you just have to accept that that’s it. That's what I mean, where not all your efforts will be rewarded. That's just the nature of it and it’s tough. But I don't think I can do what I do without that failure being part of the process, and you learn from it naturally. So I both find that frustrating, but also quite reassuring. I enjoy having to accept that. There’s joy in producing the physical print when you get it right. For me it isn’t a technical concern of getting it right rather when you look at it and it provides the response you wanted which might be something in the scene or something you’re trying to say.

JC: Do you have a preference between 35mm, medium format, and large format?

FR: Most of the images I post are medium format, increasingly more large format work that’s four by five. I like four by five. It's just not practical always so I often work with medium format. And sometimes I get something creative from 35mm which even if I took the same shot on medium format, it doesn't have the same energy to it. So I would say my favorite is definitely working in large format although I end up doing more medium format and occasionally I'm surprised by what I can get out of 35mm.

JC: Any upcoming projects, ideas, etc that you would like to talk about?

FR: So the project I’m working on right now is the release of the book, Season of the Fallen. This project went through various situations with different meanings. And then finally it makes sense when many parts of it fall together and it's actually saying something you're interested in. Beyond that, I don't know quite honestly, I've got several ideas in my mind, I find it's better just to let them form at their own time.

Participating Artist

Faraz Ravi is an artist living in the UK, interested in the changing landscape around him as metaphor for the human condition and societal change. His primary method is analogue, working with large format, medium format and 35mm cameras on black and white film. His work is mostly produced in a darkroom using traditional silver gelatin process and toning methods.