May 22–Jun 5, 2020

Online Exhibition

-

1/10: Zora J Murff, from the series, At No Point In Between

-

2/10: A Point 3, 2019

-

3/10: From the series, At No Point In Between

-

4/10: From the series, At No Point In Between

-

5/10: From the series, At No Point In Between

-

6/10: Jhalisa (talking about self), 2019

-

7/10: Roses, 2019

-

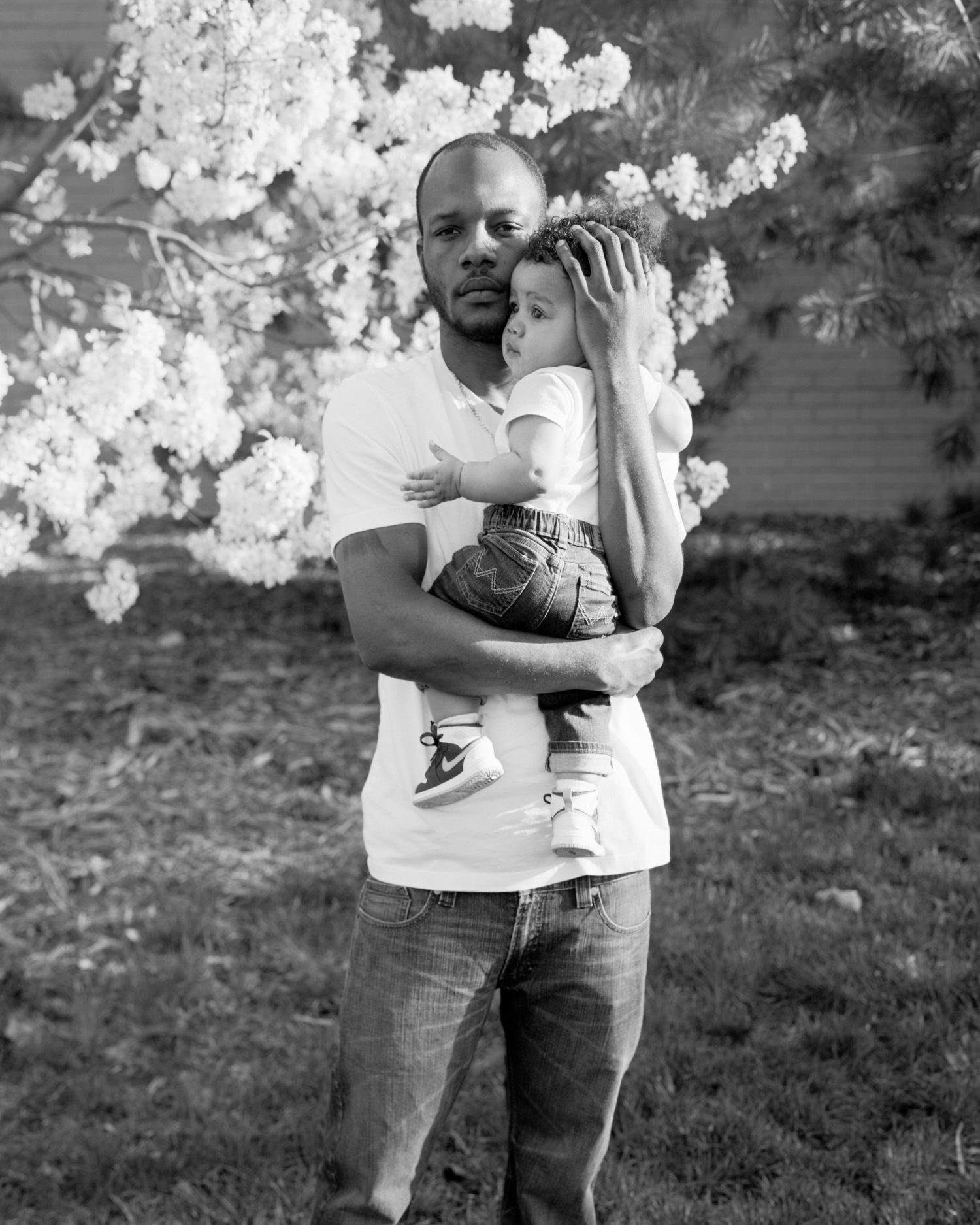

8/10: Jerrod and Junior (talking about fatherhood), 2019

-

9/10: From the series, At No Point In Between

-

10/10: From the series, At No Point In Between

Zora J Murff’s recent publication, At No Point In Between, is an expansive, tour-de-force examination of how violence and suppression are enacted towards Black communities over time. The publication masterfully fuses contemporary images, archival material, found footage, and text to bring attention to the many historical layers shaping the project. Focusing on the North Omaha neighborhood of Omaha, Nebraska, Murff unpacks the velocities and forms violence can take—immediate and explosive, as well as slow, gradual and mostly invisible. Immediate violence can take shape in the form of the murder of Laquan McDonald and Walter Scott, while slow violence can appear to us through different health crisis or mass unemployment in underserved communities. In many of Murff’s photographs within the book, the images echo the change in pace between slow and fast, moving from distinguished portraits to shots of the landscape, to close ups of building corners and urban overgrowth. Asking us to switch up our gaze in this way necessitates questions about what we choose to see and what is being hidden from us.

A significant thread running through At No Point In Between is the impact of Redlining as a devastating form of slow violence. The term refers to the practice of mortgage lenders drawing red lines around portions of a map to indicate areas or neighborhoods in which they do not want to extend loans or credit. The Fair Housing Act of 1968 states that it is against the law to discriminate against borrowers, buyers, or renters based on race, color, religion, sex, origin, disability, or other differences. Yet, this is a practice that still occurs to this day. The red lines are drawn around low income neighborhoods which coincide nearly perfectly with neighborhoods of color. Redlining is also an incredibly difficult practice to capture in a photograph, as the effects creep up, spread out, and throttle livelihoods incrementally. The photographs Murff took around North Ohama depict a real place, but they also speak to the ubiquity of this process across the United States. In a few images, we see slivers of a highway. In one image, the road snakes through the background, a thick, almost muscular line of infrastructure breaking into the space between the two housing structures on either side. In another image, it appears as a swift horizontal line, slicing through the otherwise vertical growth of trees surrounding it. Highways and interstates are methods of transportation most of us rarely consider as anything else, yet here they mark a decision making process to build something within North Omaha that would slowly displace homes and eventually negate the ability for businesses to invest in the area.

Both of Murff’s images of the highway show the roadway empty, but it is not difficult to imagine the familiar drone and blur of engines swiftly moving over them. In other images, the speed changes, and our eyes slow down. In one, we see siding peeling off of a house, and a piece of plywood in a window signaling the building’s condemnation. The curls of paint and vinyl siding, captured in stark black and white, detain our examination of the photo. They are a beautiful, fragile moment borne out of the destruction that has taken place. Further down in the image, the pace quickens, as an overgrown bush nearly bolts out of the frame, threatening to crush the chain link fence attempting to contain it. The push and pull between the faster tempo of the overgrowth, and the slow but eventual ruination of the house requires viewers to tarry a little in how readily they accept what is happening. In another image, Murff captures late afternoon sunlight sinking into the cracks of cement structures and the side of a building; the close cropping of the image rendering an almost abstract composition of lines and forms. More typical imagery of a neighborhood under duress would rush to highlight a fuller picture of the building’s decay, pushing the decline at us so fast that it barely registers. These images destabilize the logic of the stories being told, letting the information flood over us like the overgrowth, and sink in slowly, just like the sunlight.

At No Point In Between prompts reconsideration of how well we know the places and things we pass by each day. The photographs stop and start us on different pathways of understanding into how this neighborhood came to be what it is today. Changing the rhythm of how we look at these images a step farther however, are the portraits which Murff includes. Many of the photographs in At No Point In Between take great care to overcome the disinterestedness most of us have towards urban cracks and crevices, stretches of highway, or chain link fences. After spending time in these smaller spaces, looking at these portraits, brimming with connection and recognition, it can almost be disturbing to feel the turmoil of emotion they flood you with. Our gaze differs here than with other images in the publication. Looking at a man cradling a young boy or a poised young woman sitting in dappled sunlight, we start to look alongside someone other than ourselves, and acknowledge them. The neighborhood of North Omaha that we have been spending time with is not just a place that we can start to visualize, it is one that is actively inhabited.

To be seen is to be heard. Seeing is believing. There are so many adages that link the ability to see with access to some larger part of existence. What happens then, when there are forces at play that we cannot see? How do we claim access to existence when there are systems designed with the express purpose of denying it? At No Point In Between is a publication that puts heavy pressure on these questions, doing so much more than the elements briefly summarized here can convey. It engages with histories past and contemporary, and interrogates the objective truth of photography while fully utilizing its flexibility as a medium. It is a book that urges new connections to be made between bodies and the landscape they occupy, speaking to the power of building archives which analyze the circumstances in which they were made. Much like the noise of cars and trucks on the highway overpasses and roadways, At No Point In Between is a project that reverberates in our minds long after we have parted from it.

Zora J. Murff was selected for the Honorably Mentioned series by Julie Crooks, Assistant Curator of Photography at the Art Gallery of Ontario. Honorably Mentioned highlights the work of artists chosen as Honorable Mentions for Fellowship 20. Fellowship is Silver Eye's international juried photography competition. For nineteen years this competition has recognized both rising talent and established photographers from all corners of the globe, and from the state of Pennsylvania.

Participating Artist

Zora J Murff is an Assistant Professor of Art at the University of Arkansas. He received his MFA from the University of Nebraska—Lincoln and holds a BS in Psychology from Iowa State University. Merging his educational experiences, Murff uses his practice to highlight intersections between various social systems and art. He has published books with Aint-Bad Editions (PULLED FROM PUBLISHER) and Kris Graves Projects. His most recent monograph, At No Point In Between (Dais Books), was selected as the winner of the Independently Published category of the Lucie Foundation Photo Book Awards. Murff is also a Co-Curator of Strange Fire Collective, a group of interdisciplinary artists, writers, and curators working to construct and promote an archive of artwork created by diverse maker