Oct 19–Dec 31, 2020

-

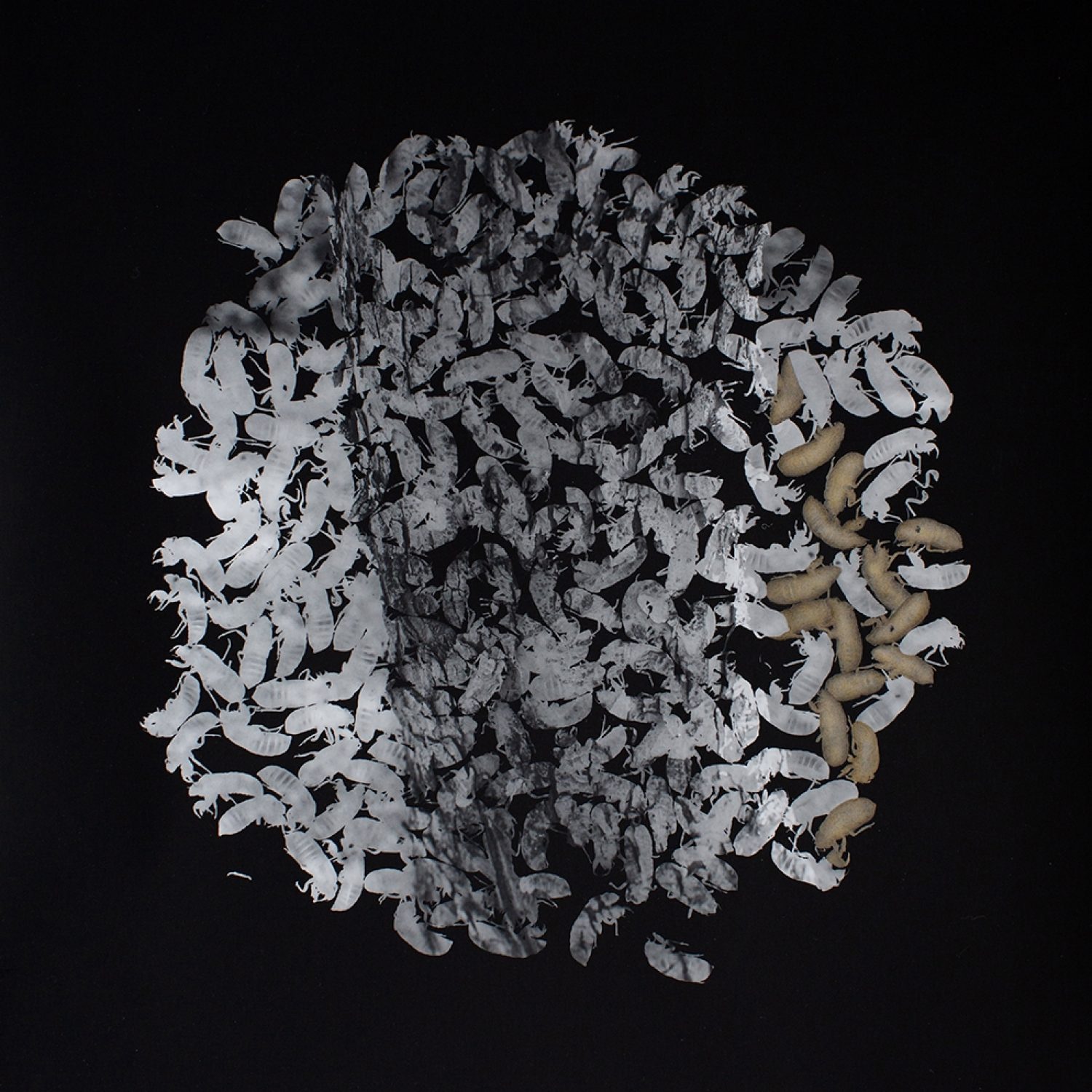

1/4: Magicicada #6

-

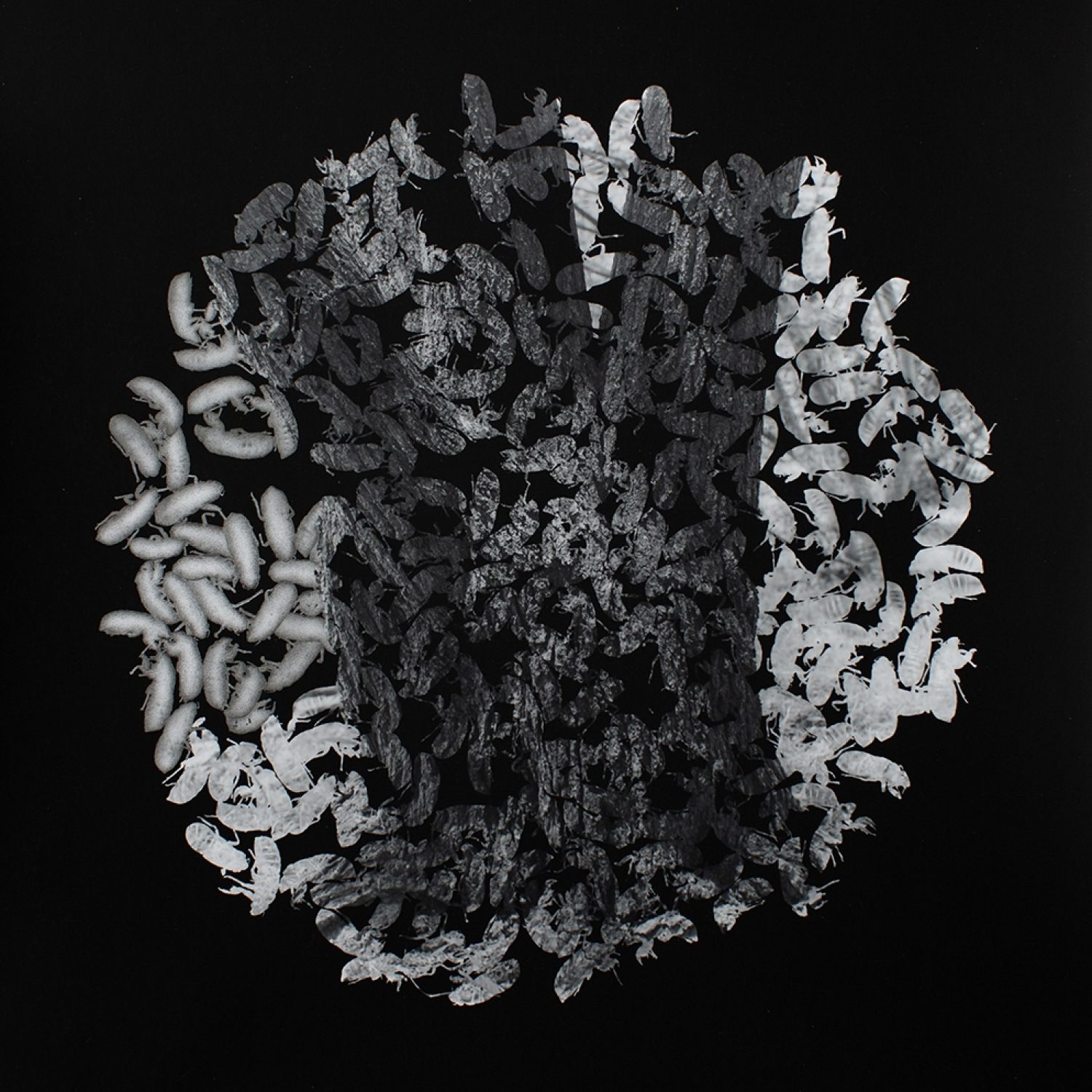

2/4: Magicicada #5

-

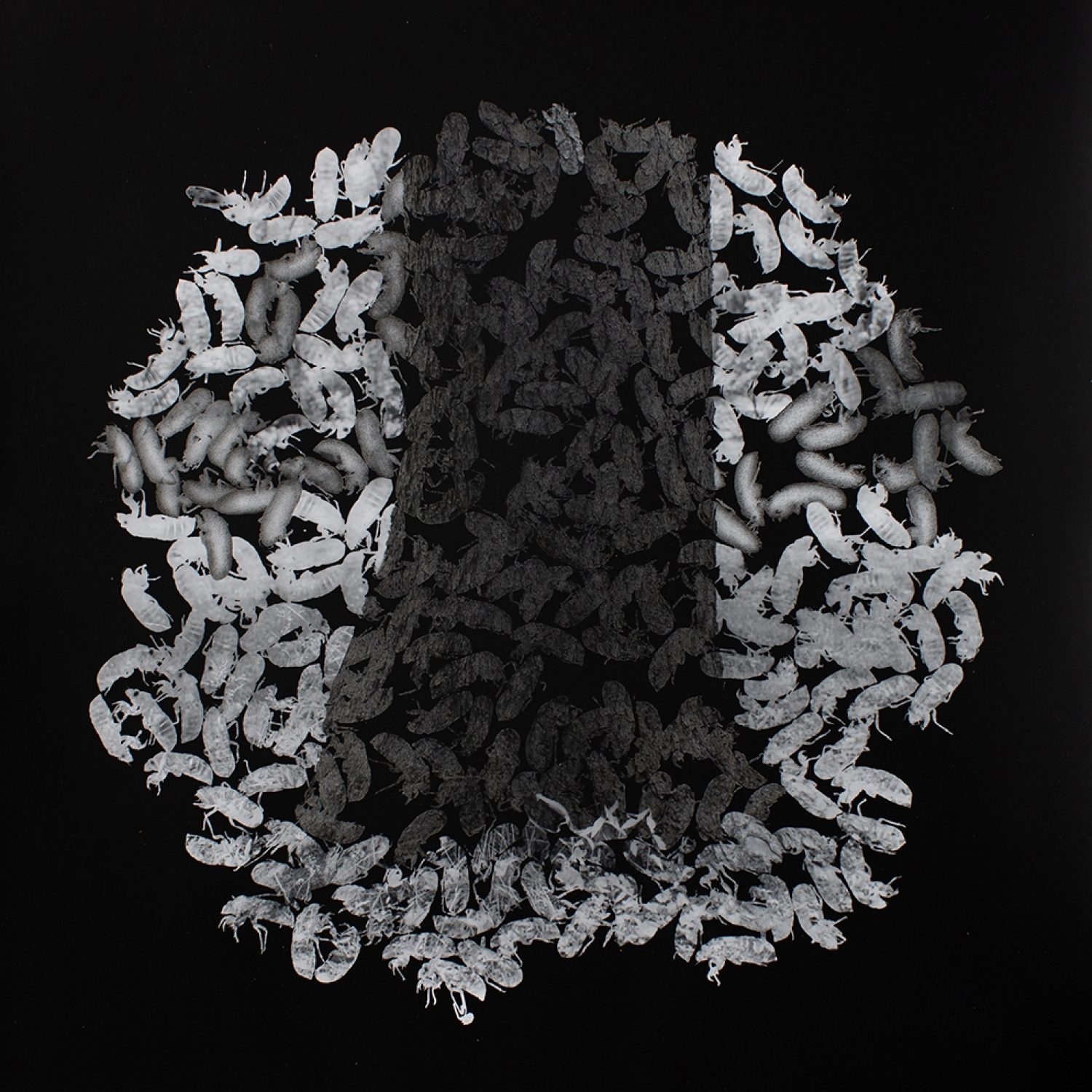

3/4: Magicicada #3

-

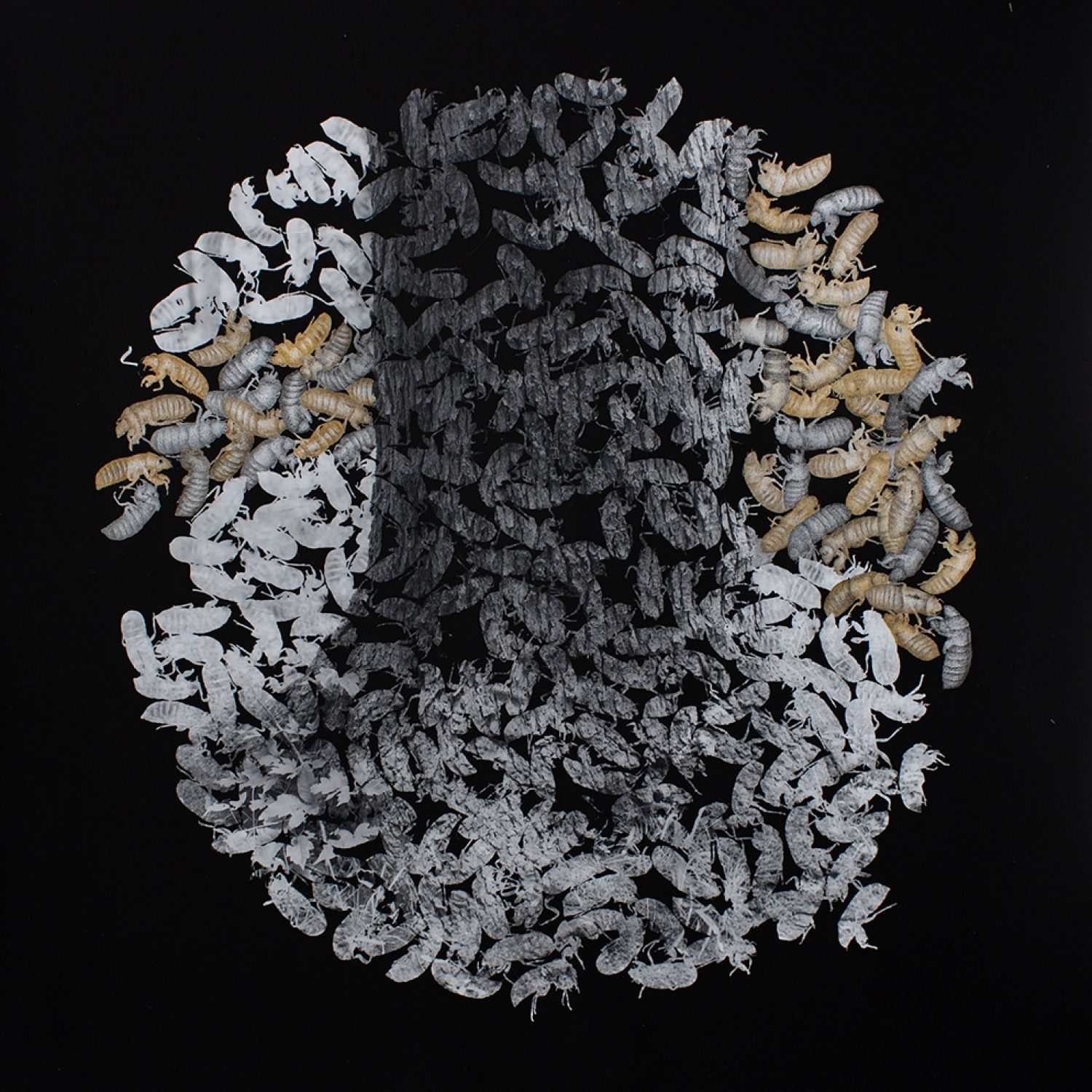

4/4: Magicicada #2

For decades, Sue Abramson has made photographs teeming with reverence for the outside world. From intimate, up close investigations of leaves and roots, to documenting the woods by her home over the course of many seasons, Abramson’s camera has lingered in natural spaces. Her latest project focuses on the emergence of cicadas, which took place around parts of North America in the spring of 2020, after the insects spent 17 years growing underground. Though the cicadas’ life span is among the longest of any insect, they spend only a fraction of it above ground, about 4-6 weeks.

During what has proved to be an unpredictable and unprecedented moment in time, it feels fitting in many ways that Abramson would choose these unusual insects as the subjects of her latest body of work. She seized the opportunity to use the impending arrival of the cicadas as the basis of her final project for a Master Gardener class she was taking through the Phipps Conservatory and Botanical Gardens. Reflecting back on her initial thoughts for the project, Abramson admits, “I thought about [the cicadas] more as a science fiction or horror movie… but after I did the Master Garden program and now that it’s 2020, we all really need to have a lot more respect for insects. Everything is connected, they have such an important role to play.”

With this shift in her mindset, Abramson still needed to find the cicadas, and went about conducting research. She interviewed and spoke to experts such as Robert Davidson, the collection manager for the Section of Invertebrate Zoology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, as well as Ryan Gott, an entomologist and the Associate Director of Integrated Pest Management at Phipps. Learning that cicadas start to emerge when the ground temperature reaches 65 degrees, she started looking in early May. The anticipation for the first sighting really started to build as Abramson reflected on the last time that she had seen the insects. She wished she had a camera on her 17 years ago, and after the event had ended she could only wait for 17 years until the next emergence.

Despite her research and planning Abramson largely missed the moment of the cicadas emerging in large numbers. In her mind's eye, she had a picture of what it would look like to come across hundreds of cicadas emerging from the ground all at once. Regardless of her putting the word out that she was looking for cicadas on social media, tracking appearances of the insect on an app called Cicada Safari and a website, she was never able to encounter the image she had set up in her mind as the one she wanted to photograph. This is a fact she laughs off, but feels strangely heartbreaking. In the year of 2020, when time can seem nonexistent, or sped up, or stalled out, the thought of an artist patiently waiting for this specific moment for 17 years to occur seems like a heroic feat, and for them to miss the moment they had been waiting for–that seems supremely unfair.

Undaunted, Abramson pivoted again, and decided to work with cameras that she hadn’t used for almost the same amount of time that the cicadas had been underground. She filled her trunk with film cameras of all kinds: a zone zero camera, a pinhole camera, and a 4x5 field camera. As she continued to look for the insects, Abramson realized that what she was finding more than the cicadas themselves were the insect’s exoskeletons, which are shed as they climb up and into the trees to eat, sing, and mate. Littered around the trunks of trees are piles and piles of these exoskeletons, which Abramson collected. Later on, in the darkroom, she printed images of the trees she had taken, and halfway through the exposure, would lay the exoskeletons down around the base of the tree, creating a circular pattern reminiscent of a microscope. As a final act of adjustment, after so many starts and stops to the project as a whole, Abramson filled in areas of the print where the exoskeleton hadn’t come through as clearly with graphite, creating a beautiful silvery surface in parts of the print. The light catches the graphite making that small area shimmer, twitching with a little bit of life.

Much of Abramson’s past work has acted as a kind of witness to the emotions of grief and loss. The woods and fields that have been her subjects in the past often feel like collective sites, as Abramson has turned her own personal moments of pain into spaces and images others can find solace in. The genus for cicadas is called Magicicada, which is also what Abramson has chosen to title this body of work. These images contain elements of the previous work she has made–life and death and the natural world are all present–yet the emotional tone has shifted. This work is the result of years and years of patience, failure, perseverance, and the kind of quiet triumph that takes place in special places like the darkroom, or the woods. Somehow, the feeling you come away with after viewing these photographs is hope. The story behind them is full of twists and turns, moments of disappointment, and stokes of ingenuity. Even the exoskeletons themselves feel like a strangely optimistic symbol: a past life shed as the insect crawls toward an unknown future.

-- Kate Kelley, Assistant Curator, Silver Eye Center for Photography

The Lab Presents celebrates the Lab @ Silver Eye Member Artists, providing a space for their work to be engaged with by our community. The Lab @ Silver Eye is the only workspace in the region where members can access museum quality printing, scanning, and print finishing equipment for affordable DIY use as well as professional development opportunities. The Lab also offer workshops and full service printing, scanning, and framing.

Participating Artist

Sue Abramson is a fine art photographer working in Pittsburgh. For four decades she has produced imagery relating to the environmental landscape using a variety of methods. Abramson’s book, A Woodlands Journal, is a decades long photographic meditation on her evolving relationship with light, loss, chaos and place. Her body of work, From the Same Bulb, includes garden work made in response to personal grief and a life in transition. Under the name Fstop Gspot, Abramson has created a font made from speculum. She uses these letters to produce merchandise that raises funds for women’s reproductive health organizations.

Widely exhibited, Abramson’s photographs have been acquired for many permanent collections, including The Carnegie Museum of Art, The Polaroid Corporation, University of Pittsburgh, Biblioteque Nationale, and Blue Cross of Western Pennsylvania. Her exhibited work has been nationally and internationally shown. Featured exhibitions include “ The Only Constant is Change” at The Westmoreland Museum of Art, “Gestures 15” at the Mattress Factory, “Digital to Daguerreotype" at The Carnegie Museum of Art, and “No Mirrors” at Rayko Photo Center. She is retired from her Associate Professor of Photography position at Pittsburgh Filmmakers, where she taught for 30 years.