May 18–Jul 18, 2023

-

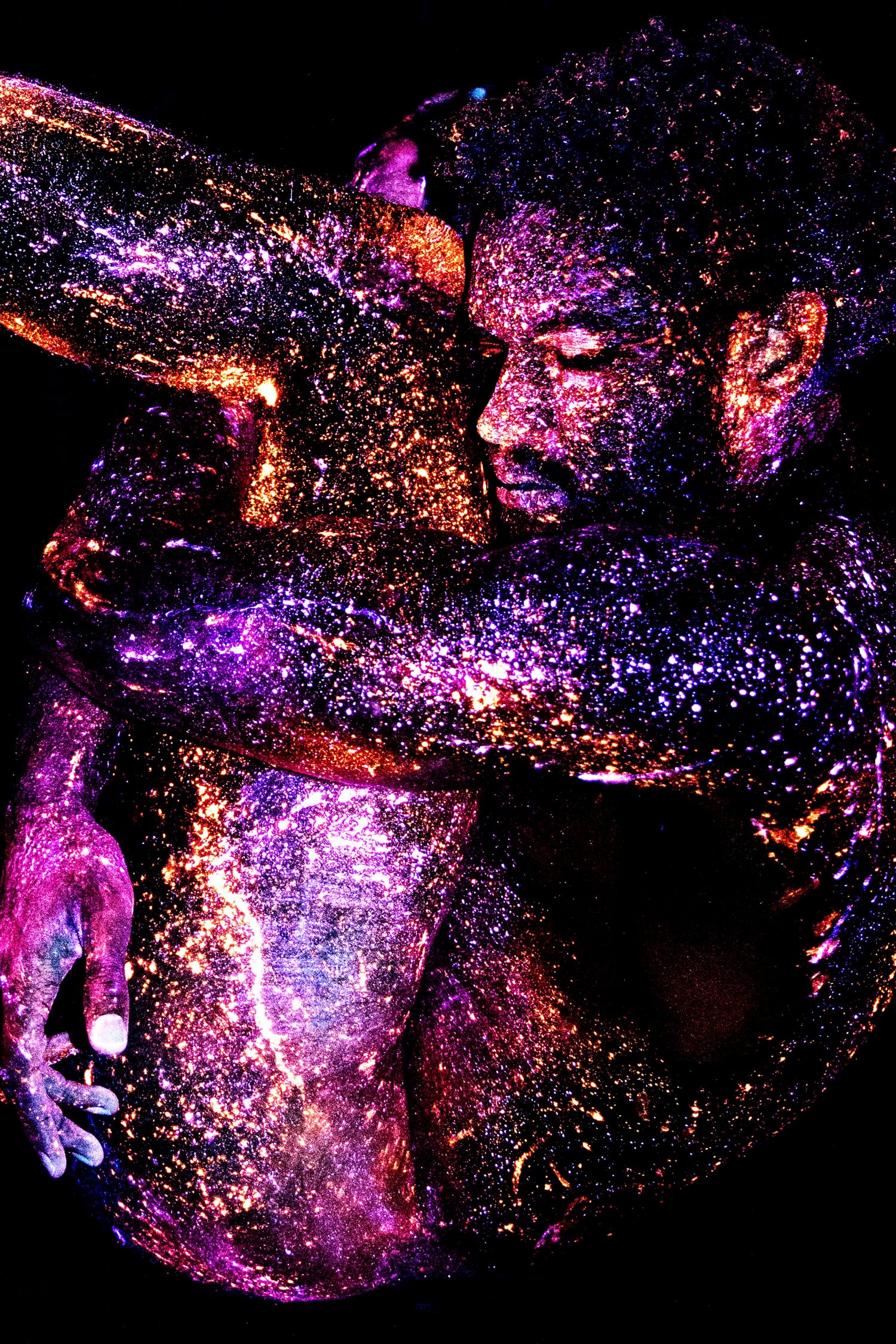

1/9: Mikael Owunna, Anagonno Alagala (Anagonno of the Sky), 2021 (From the series Cosmologies)

-

2/9: Mikael Owunna, The Vision of Innekouzou, 2017 (From the series Infinite Essence)

-

3/9: Mikael Owunna, Amadi - Queer Nigerian (Pronouns: she), 2017 (From the series Limitless Africans)

-

4/9: Mikael Owunna, 4 Queer African Women in the Snow, 2017 (From the series Limitless Africans)

-

5/9: Mikael Owunna, The Martyrdom of Eke-Nnechukwu, 2021 (From the series Cosmologies)

-

6/9: Mikael Owunna, Valu (Roan Antelope), 2021 (From the series Cosmologies)

-

7/9: Mikael Owunna, The Resurrection of Eke-Nnechukwu, 2021 (From the series Cosmologies)

-

8/9: Mikael Owunna, Amma's Womb, 2017 (From the series Infinite Essence)

-

9/9: Mikael Owunna, The Flying African, 2018 (From the series Infinite Essence)

What would it look like if you could imagine a world in your perfect image?

Would it be a world of light and/or darkness? Would your creation stories be your guidelines? Or would the tools artists use be wielded as weapons of resistance to institutional erasure?

In the world that Mikael Owunna imagines, Black bodies are transformed from targets of physical and emotional violence into cosmic vessels and opportunities for community building. The Nigerian-Swedish-American artist and Pittsburgh-based photographer throughout his practice focuses on developing work in conversation with issues surrounding identity, representation, and diversity.

With the click of a flash, Owunna turns art into activism, fantasy into hope, and reimagines the past as the starting point for a better present and a future with infinite potential.

In this interview, conducted by Silver Eye Scholar and the University of Pittsburgh graduate Dominique Swift, Mikael speaks about the universe he is creating and how the camera serves as a tool for emotional and physical discovery. Swift writes:

"The first time I saw Mikael Owunna’s work; it was a shocking experience. I was walking past Everyday Café in Homewood and saw his images and I remember being stopped in my tracks by their beauty. It felt so impactful for me as a Black woman to see artwork representing seemingly powerful Black people in a predominantly Black neighborhood. I couldn’t help but wonder what the world would be like if we could all see ourselves that way."

Growing up, Mikael was enamored with the whimsical worlds of movies like Harry Potter, shows like Dragon Ball Z, and video games like Final Fantasy. Imagining himself as part of these magical spaces, in turn, made Owunna see himself as a magical being.

Dominique Swift: How does the goal of representation play into your process of image-making? You imagined yourself in these spaces, but would you say that your art is making it a reality to be seen by people of color?

Mikael Owunna: There are no Black people in those worlds. I feel like I'm thinking about how to create and build a universe around the work, and around these cosmologies. I think one of the things that I appreciate about those artistic modalities, be it video games or fantasy series is that you're building a universe. And I think that is where you have so much flexibility in terms of gaining access to people. Because, as Black people, it's imperative that we get re-grounded into our accurate understanding of Blackness and who we are, and recalibrate our entire sense. How do we build a universe where we accurately understand and can visualize, see and carry that with us everywhere we go?

DS: I know a part of the inspiration that catapulted you into the idea of Infinite Essence was the tragic murder of Michael Brown and how his body was left in the streets for hours like a spectacle. Can you talk about how that event played a role in your want or need to create a project like Infinite Essence?

MO: Yeah, when Michael Brown was murdered, I think I was living in DC at the time, and I just remember the photo being shared of his body on the street. Then the media took pictures of the body and then they published them without any consent. It just showed the level of disrespect for him, his family, for Black communities. And so I wanted to think about how to visually reimagine what Blackness is beyond this sight and container of death, to be the source of all life itself, the source of creation, the blackness of outer space, the blackness of the womb, which creates life, the blackness of the deep ocean, the blackness of the earth. And so that was part of the project that then began to become integrated with the research I was doing into African spiritual systems. And the understanding that we have multiple spiritual bodies and thinking about how we actually kind of depict a spiritual body that's invisible to the human eye. That's what made me start thinking about using or building tools that could visualize the invisible to showcase this alternative vision of Blackness. But it was really kind of sparked by police brutality.

Originally trained as an engineer, Owunna built a camera flash that only transmits ultraviolet light, which when used, exposes hand-painted bodies of nude Black models with fluorescent paints. With this camera that Owunna has likened to a magic wand, he illuminates clandestine cosmologies on Black skin and leads the viewer to wonder what else have we been too colorblind to see.

MO: One of the models featured in Infinite Essence after the process when looking at their photos, told me that their whole life they dreamed of being able to see themselves as the universe, and that every Black person deserves to see themselves in this way. And it took a total recalibration of historical narratives and understanding of who we are. And when I did my photo shoot, I had my eyes closed, and then I could still see my glowing arm emerge from the blackness. It was a very spiritual and healing experience to think about how the artwork, when connected to this larger paradigm of myth and cosmology, as our ancestors thought about the artwork in that way, can be used as a conduit for spiritual development, cultivation, and mental and physical health and transformation.

DS: Do you view your work as inherently political?

MO: I think it's political in a way that people might not conventionally understand politics. Because ultimately, when you rebuild a universe you start to see your work as building an alternative. The goal is for that to then become superimposed upon the physical reality in which we live as well. I think it is also a call for destruction and recreation because I think that, at least, a hope for the work is that people are like, oh, what does that future look like that we want? And I'm building this universe that can provide an answer for people.

Much of Owunna’s work is an illustration of the beauty of coexistence: science and art, history and future, and African culture and queer identities.

DS: How have your personal identity and experiences influenced your artistic practice? And what message do you hope to convey to work like Limitless?

MO: My first photographic series, Limitless, was born out of my experience as a queer Nigerian person; and when I was 18, out of my family. I was put through a series of exorcisms due to my sexuality and to drive the gay devil out of me, and so I really struggled with thinking that I didn't have a right to exist. Six months after those ceremonies, I found a camera and the camera became this lifeline for me. It sparked a whole new space of emotional refuge at a time when I felt really lost.

And so I was always thinking about photography and how it could be a way for me to visualize an alternative world that was beyond the emotional, spiritual and psychic space that I felt that I was trapped in at the time. From a documentary perspective, it really came down to okay, I want to think about how could I build a body of images, that would have been a resource for me when I was younger. And to know that, you know, I wasn't isolated, I wasn't alone. And it also became, again, this joint historical building, historical archive for the contemporary narratives. But then also, like I do in all my work, connecting it to the past.

The photographic series Limitless Africans celebrates the beauty and diversity of African cultures and challenges negative stereotypes and misconceptions about LGBTQ Africans. By placing contemporary identities and stories in a greater and irrefutable historical narrative Owunna cements the legitimacy of their personhood through his work which he refers to as an archive for future generations.

DS: When it comes to art, I think a lot of people just want something that’s beautiful, which of course is a valid desire. But to me “beautiful” can easily become boring, when there is no meaning behind action and image. Do you ever struggle with that balance? Or do you just feel some sort of responsibility to make your work have meaning or to make meaningful work?

MO: Yeah, I think for me, every piece is so intentional because that's also how this larger history so I think that's also why this connection to the past is really important in the work because within tradition small African knowledge systems, you could think about mythology as being this system of knowledge that would integrate art, science and religion as a way to transform human consciousness. For example, in Ancient Egypt all of the images that surrounded you are created with divine ratios within them, and you see images of yourself as a god, everywhere you go. As artists, we are these divine conduits that can either destabilize, you know, people with, you know, profit when you see like, the advertising through like cigarettes, or all these other things that kind of surround us, or can be a catalyst for people's spiritual development and cultivation.

DS: What advice would you give aspiring photographers and artists interested in exploring themes of identity representation and diversity in their work?

MO: I feel like a big part of it comes down to the research. And I think, first of all, what's the question of identity that you're trying to look at? Is it something related to you? I think it is usually more powerful when it's connected to the person. And then also doing extensive historical research around what that identity looks like, how it's been one of the factors shaping it, and the other artists that have worked in that space. Because your work is going to be in conversation with them, still you also want to develop a distinct visual style and artistic voice.

Mikael Owunna is currently focused on exploring film, dance, and sculpture as his work develops to find new ways to tell old stories that have the possibility of new meanings.

Participating Artist

Mikael Owunna is a Nigerian American multimedia artist, filmmaker, and engineer. Exploring the intersections of technology, art, and African cosmologies, his work seeks to elucidate an emancipatory vision of possibility that revives traditional African knowledge systems and pushes people beyond all boundaries, restrictions, and frontiers.